According to the author’s note at the end of the book, Yoko Ogawa has won every major Japanese literary award. Her fiction has appeared in The New Yorker. Her works include The Memory Police; The Diving Pool, a collection of three novellas; The Housekeeeper and the Professor; Hotel Iris; and Revenge. She lives in Ashiya, Japan.

When I picked up this book from the library, the author’s name felt familiar. Then I realized—I had read two of her books 14 years ago! Yet, I have no recollection of them. So, this blog entry is written as though I am approaching her work for the first time.

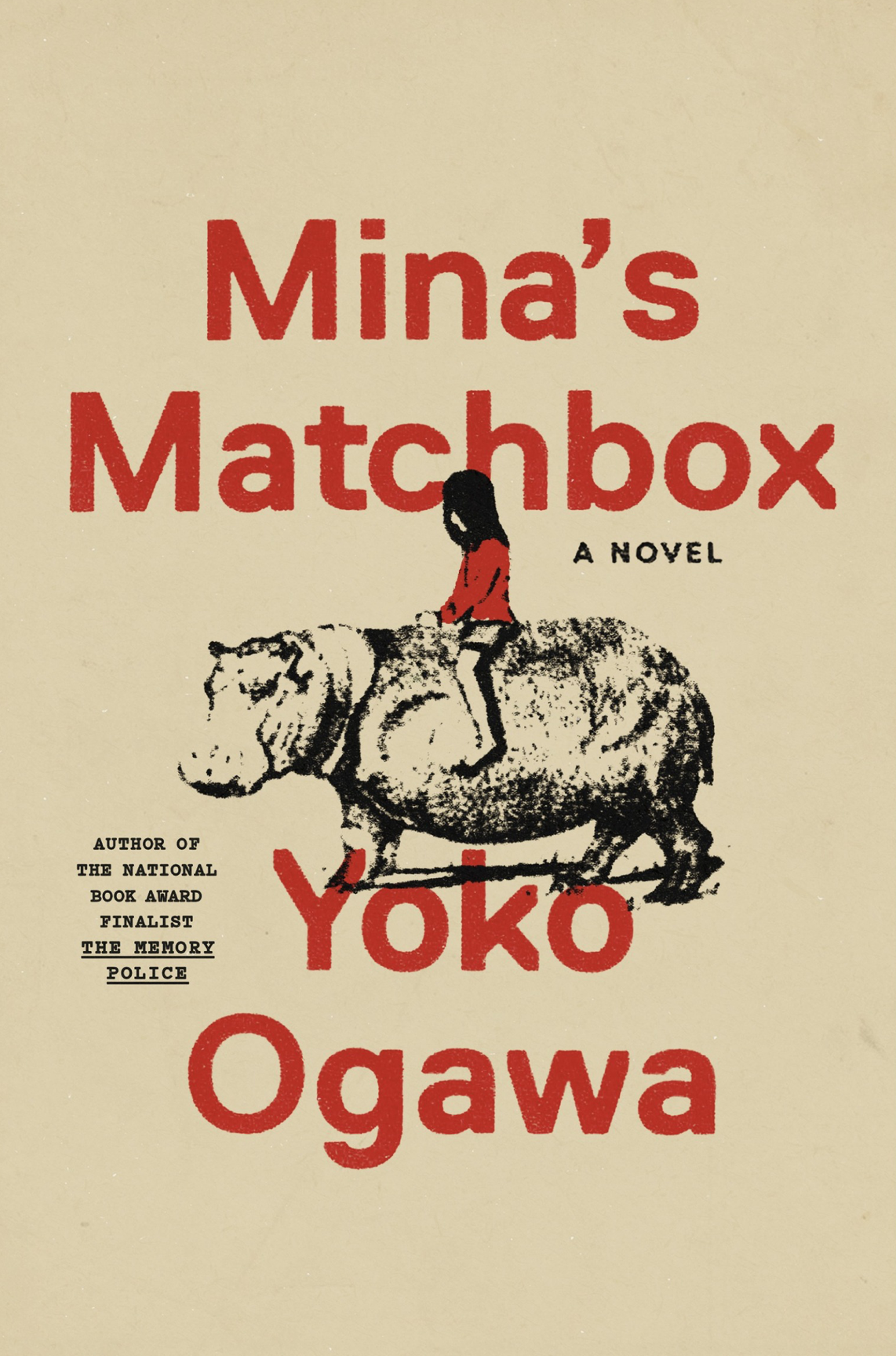

Back in 1972, a young girl named Tomoko moves into her cousin Mina’s house in Ashiya. Through Tomoko’s narration and her interactions with Mina, her family, and friends, we see the world through her observant and curious eyes. To me, Mina’s Matchbox reads like a series of vivid and evocative short stories about Tomoko’s day-to-day life. Characters and places come alive through her narration. My favorite part is when Mina invents imaginary stories based on the matchbox designs she has collected over the years—hence the book’s title.

If there is one common theme connecting the story’s snippets, it would be the various types of vehicles woven throughout the book. As Yoko Ogawa writes:

The first vehicle I ever rode in was a baby carriage that had been brought across the sea, all the way from Germany. It was fitted out in brass and draped all around with bunting. The body of the carriage was elegantly designed, and the interior was lined with handmade lace, soft as eiderdown. The metal handle, the frame for the sunshade, and even the spokes of the wheels all glittered brilliantly. The pillow was embroidered in pale pink with the characters for my name: Tomoko.

The carriage was a gift from my mother’s sister. My aunt’s husband had succeeded his father as the president of a beverage company, and his mother was German. None of our other relatives had any overseas connections or had even so much as flown in an airplane, so when my aunt’s name came up in any context, she was always referred to as “the one who had married a foreigner”-as if the epithet were actually part of her name.

In those days, my parents and I were living in a rented house on the outskirts of Okayama City, and the carriage was more than likely the most valuable object among our possessions. A photograph from the period shows how out of place it looked in front of the old wooden house.

It was far too large for the tiny garden, and it was far more eye-catching than the baby herself, presumably the subject of the picture. I’m told that when my mother pushed the carriage in the neighborhood, passersby turned to look at it. If they were acquaintances, they’d invariably come up to touch it, commenting ecstatically on how beautiful it was before moving on, without any mention of the baby inside.

Unfortunately, I have no memory of riding in the carriage. By the time I became aware of what was happening around me, that is, by the time I’d grown too big to ride in the carriage myself, it had already been relegated to the storage shred. (Mina’s Matchbox, p. 1)

From the baby’s carriage on page one to the train, her uncle’s Mercedes-Benz, and even Mina’s hippo, vehicles continuously carry the story forward.

Mina’s Matchbox is not a page-turner. It’s not the kind of book that compels you to read it in one sitting. There is no grand resolution from a storytelling perspective. Yet, it offers a heartwarming glimpse into the days of a young girl—reminding me of a time when I, too, was once young and endlessly curious.